One of the most fascinating aspects of animation is the creation of visual continuity and motion, through still images. While technology may have changed the way animation works today, it hasn’t changed the underlying mechanism of the craft. If you’ve ever seen anything move on screen, persistence of vision is at play. So, what is persistence of vision?

To start, it’s the very foundation of animation, but as an animator, how do you use it? How do you create that smoothness from frame to frame? It takes some understanding of a pretty basic optical concept that’s been at play for well over 100 years. Let’s take a look.

Defining Persistence of Vision

How we perceive motion on screen

You don’t need to be an animator to understand the fundamentals of animation. If you’ve ever created a flipbook, you’ve used persistence of vision. It is the basis for animation, motion picture technology and cinematography, going back to the earliest forms of entertainment.

PERSISTENCE OF VISION DEFINITION

What is persistence of vision?

Persistence of vision is the optical phenomenon where the illusion of motion is created because the brain interprets multiple still images as one. When multiple images appear in fast enough succession, the brain blends them into a single, persistent, moving image.

The human eye and brain can only process about 12 separate images per second, retaining an image for 1/16 of a second. If a subsequent image is replaced during this time frame, an illusion of continuity is created.

Ways to create motion with persistence of vision:

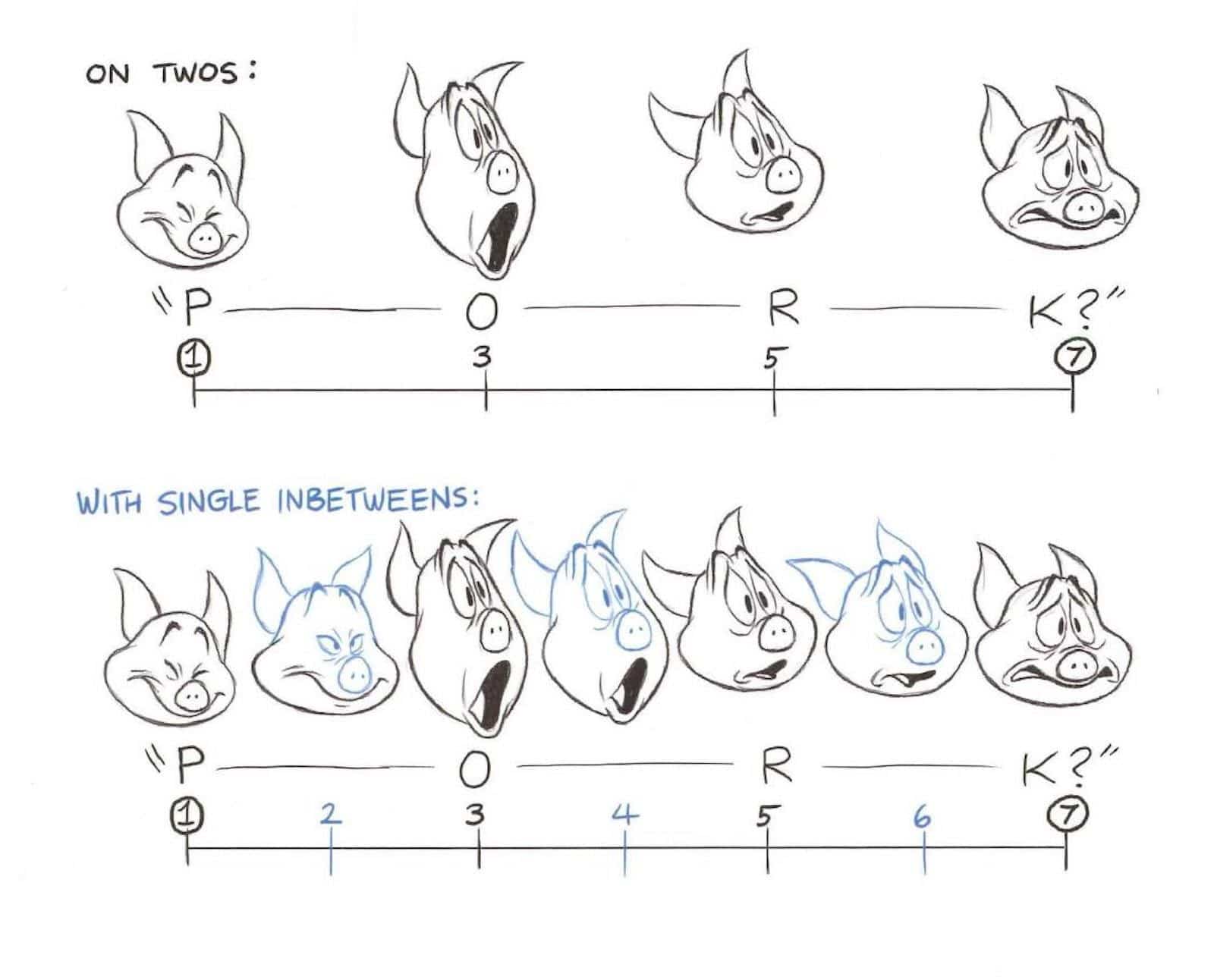

- Animating “on twos” — when one image is shown for every two frames at a total of 12 frames per second, it allows for smooth motion

- Animating “on ones” — when one image is shown for every frame at a total of 12 frames per second, it allows for even faster motion

It’s not always necessary to draw one image for every frame unless you need quick motion. Drawing one image for every two frames meets the requirement of the eye to perceive smooth transitions. You can tell in this example below that animating "on ones" will be much smoother than animating "on twos."

More frames equals smoother motion

Anything slower than this (“on threes,” “on fours”), the motion will appear choppy and interrupted.

The window where we no longer notice the images as separate images, but instead as one smooth persistent moving image is the sweet spot. If we can use a frame rate faster than what we can typically retain, we will trick the eye and mind that the images are in fact moving.

So, how many frames per second can the human eye see? The human eye isn’t a camera. And it’s far more complicated than a quick calculation. The video below breaks this down, providing some interesting persistence of vision examples.

What is persistence of vision?

Based on the experiment in the above video, about 10 frames per second was when we stopped noticing the space between each image. But it was at 24 when the animation was the smoothest. This is a typical minimum for most animations, if not, much faster.

Practicing Persistence of Vision

Using the illusion in animation

Deciding how you want to animate is up to you. Generally higher budgets, like Disney films, will animate on one’s, while most other films will use two’s. Anime typically uses three's, as they tend to be lower budget, but the details of the drawings often balances that out.

Let's look at a persistence of vision example in action. Animation feature film director, Aaron Blaise, takes us through his process of how to animate a character turning his head, drawing by drawing.

Persistence of vision in action

If you’re not quite as advanced like a visual artist, you can still experiment with persistence of vision. Flipbooks are an easy way to see the concept at work, but also they’re not too difficult to pull off. YouTube, animator, Andymation takes us through his process.

Persistence of vision in flipbooks

Before people were creating Disney movies and flipbooks, inventors from as far back as the 18th century were experimenting with this optical illusion.

A Bit of History

Early optical toys and experiments

In the 19th century, English-Swiss physicist Peter Mark Roget, described persistence of vision as a type of eye defect that showed moving objects looking still when they reached a high enough speed. Think of a ceiling fan. You can’t tell how many arms it has when it’s spinning at its highest speed, but once it stops, it’s clear there are several arms.

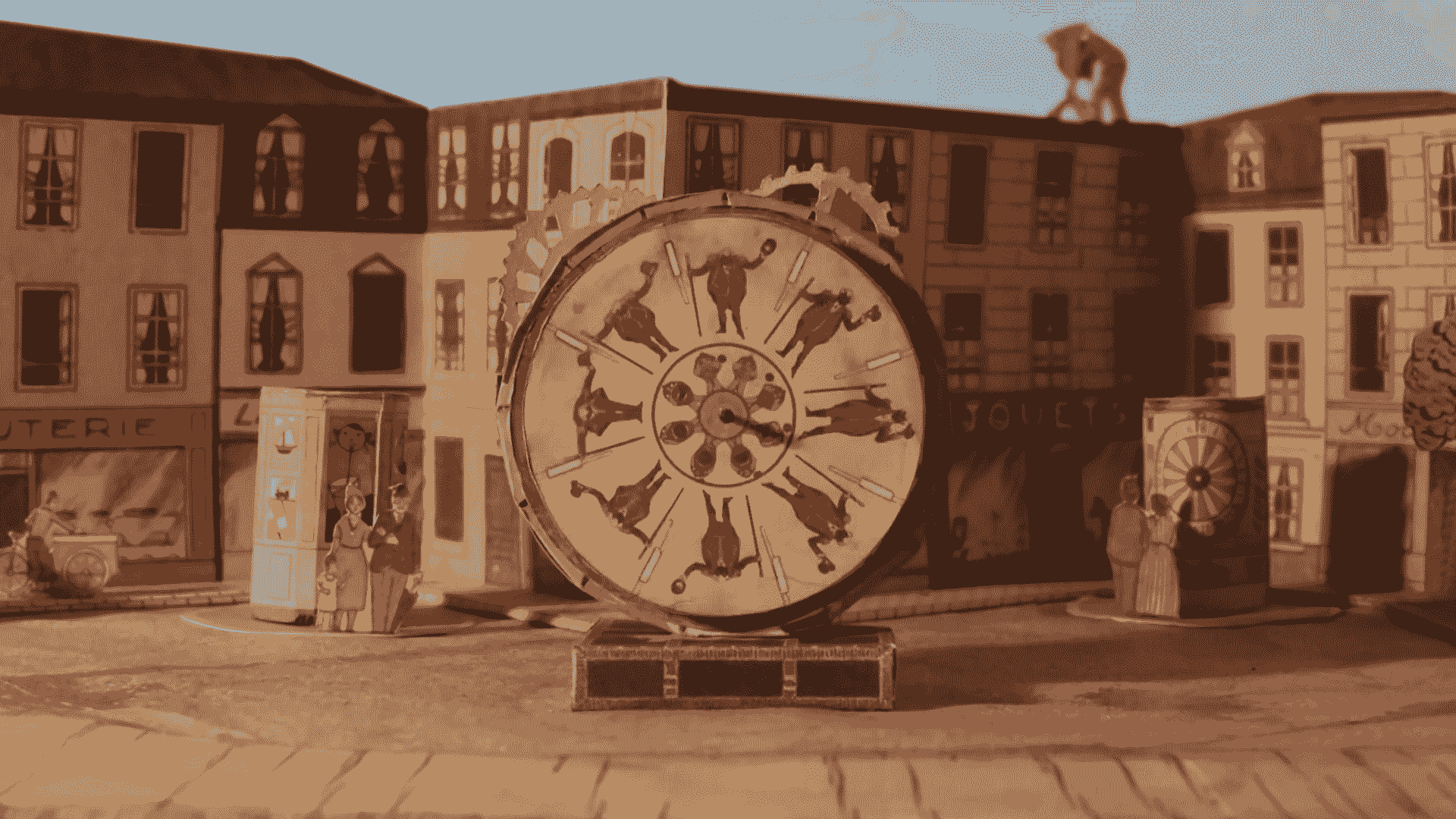

But the opposite is of course, also true. Seeing individual images at a high speed creates the illusion of motion. Joseph Plateau’s invention of the phenakistoscope shows us this. With individual drawings placed on a circular disk and spun, the drawings would appear to be moving.

Earliest animation • The Phenakistoscope

These theorists focused more on the eye retaining the image. However, it has been discovered that this phenomenon has less to do with how long the brain can retain an image than it does with how the brain interacts and computes all of the data once retained. It is this constant and complicated computation that creates persistence of vision.

Later, in the early part of the 20th century, German theorists like Max Wetheimer and Hugo Munsterberg concluded that this process actually takes place behind the retina, with the brain being the powerhouse behind the illusion.

The eye takes in many different experiences—color, light, depth, form and motion. All of this data is sent to different areas of the brain. It’s this consistent flow and communication between different pathways and areas of the brain, that give us our unique perception and ability to witness such phenomenons.

And lucky for us, these phenomena can create some pretty amazing entertainment (e.g., animated films)! And there’s obviously quite a bit more that goes into animation, so let’s explore that next.

UP NEXT

History and types of animation

Now that you understand a fundamental principle in animation, let’s explore a little more. From Mickey Mouse to Coco, how are they made, and how did animation techniques evolve over time?

Up Next: Types of Animation →

Showcase your vision with elegant shot lists and storyboards.

Create robust and customizable shot lists. Upload images to make storyboards and slideshows.