Greta Gerwig’s adaptation of Louisa May Alcott’s “Little Women” is a story of ambitious women and the birth of an artist. Of course, these themes are at the heart of the original work, but Gerwig’s Little Women screenplay strategically reconfigures the familiar narrative; the cozy classic becomes fresh and thrilling. How does Gerwig’s Little Women adaptation both hold true the original tale, while also grounding the story in present day filmmaking? Read the script and check out our analysis below to find out.

Who Wrote Little Women Script?

Written by Greta Gerwig & Louisa May Alcott

Greta Gerwig is a writer, actress, director, and playwright known for her performances in and development of coming-of-age, relationship focused mumblecore films, like Lady Bird, Frances Ha, and 20th Century Women.

Alcott was an American novelist, poet, and short story writer who found her passion in writing at an early age. Best known for Little Women, Alcott paved the way for free-thinking, ambitious heroines, and challenged societal standards of the stereotypical female character. She published over 30 books and collections of poems and short stories in her lifetime.

Script Teardown

STRUCTURE OF LITTLE WOMEN SCREENPLAY

With all the time skips and parallel timelines, you definitely may be asking yourself, “What is Little Women about?” Here is the basic story structure for the Little Women plot:

Exposition

Present: Jo March is a writer and she attempts to sell her book to Mr. Dashwood (he drives a hard bargain). Her sister Amy is in Paris with Aunt March, working on her art, Meg March lives with her husband and children, and Beth March is ill. Jo March feels her duty is to keep her family afloat.

Inciting Incident

Past: Jo and Laurie meet at a party. Jo’s father is at war and Jo is upset that she is a girl.

Plot Point One

Present: Jo gets a letter from home informing her that Beth’s health has taken a turn for the worst. Jo makes her way home from New York.

Rising Action

Past: Laurie becomes close with the March sisters.

Present: Meg is tired of being poor, Amy tells Laurie she may quit art entirely. Jo writes and sells her hair to get more money for her family while Beth is sick.

Midpoint

Past: Beth has Scarlet Fever. Aunt March tells Beth that she has to save her family because Jo, Meg, and Beth will not be able to.

Present: Laurie tells Amy not to marry Fred. Beth feels like she is running out of time. Jo tells Beth she has stopped her death before.

Plot Point Two

Present: Amy turns down Fred’s proposal, but Laurie has left for London.

Build Up

Past: Meg gets married. Beth’s fever is getting worse, but she lives. Jo feels lonely, but turns Laurie down. Amy leaves for Paris.

Present: Meg sells her prized piece of fabric to help keep her struggling family financially stable. Beth’s dies. Jo quits writing because she couldn’t save Beth, and thinks she may have been mistaken about turning Laurie down; she writes him a letter saying she can be with him. Aunt March is ill.

Climax

Past: Jo meets Friedrich, her professor.

Present: Amy and Laurie marry. Jo makes a compromise with Mr. Dashwood and he buys her book.

Finale

Present: Jo’s book, titled “Little Women,” is published. They open a school in the home Aunt March left to them after her passing.

Little Women Script Takeaway #1

Themes in Little Women

The truth is Little Women is a story about an artist, but at its core, it’s also a story about gender and money. Scattered throughout the Little Women plot are mentions of what it means or feels like to be poor, considerations of whom to marry based on financial standings, and how to make career moves as a woman in the Civil War era. As is the case in most screenwriting, none of the following Little Women quotes/lines are coincidental:

- “It’s so dreadful to be poor.” — Meg March

- “I can’t afford to starve on praise.” — Jo March

- “I understand queens of society can’t get on without money, but it does sound odd coming from one of your mother’s girls.” — Laurie

Aside from dialogue, general situations in which the March girls find themselves revolve around money. Jo tries to sell her book (which she is told she cannot sell unless the female protagonist is married by the end). She sells her hair to get money for her family when Beth is sick.

Meg and John struggle with poverty. Aunt March tells Amy she is the sole hope for her family’s survival (she’ll save them by marrying appropriately, unlike her mother).

And despite their own monetary struggles, the March women uproot their own Christmas in order to provide for a poor woman and her children nearby.

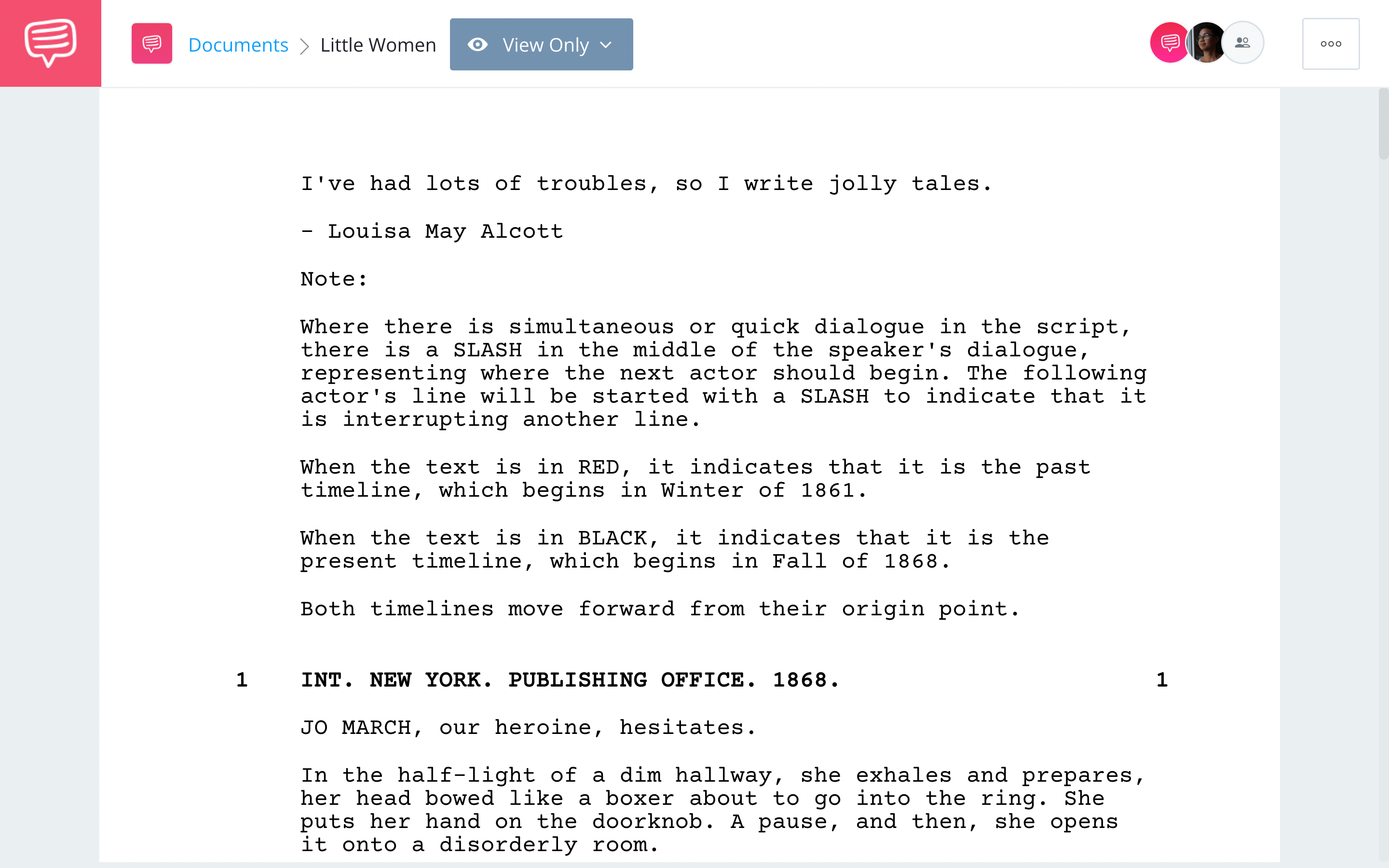

One scene in particular pulls these inner workings of Little Women out to the external, and that is when Amy tells Laurie she is considering giving up on her art. In the video below, Amy tells Laurie she always understood her place as a woman, and that she won’t test that societal standard by forcing her art in the world if no one will have it.

Marriage is an economic proposition • Little Women

A few lines in this scene especially pinpoint not just Amy’s outlook on life as a female artist, but about the time in which they live.

We uploaded the Little Women screenplay into StudioBinder’s screenwriting software to take a deeper look. Amy, like her family, understands that there is something to be said for art and money, and then there is something to be said for supporting themselves. Read the entire scene by clicking the image below.

Little Women script • Read Little Women Theme Example

As it stands, these concepts cannot occupy the same space, and thus the tension and dramatic question of the Little Women script is fortified: they know what and who they love, but is it enough?

Can these women do what it takes to live life to the fullest, do what they love, marry (or not marry) as they see fit, while also living in a world that sees them as nothing more than an “ornament to society”?

Little Women Script Takeaway #2

Little Women as an adaptation

The Little Women screenplay straddles the line between familiar and classic, and exciting and relevant. It’s a remarkable example of how to create a bold adaptation of a beloved work. Of course, there are a few aspects to consider with adaptations.

The film version of Gerwig’s Little Women is mostly faithful to the original work. Does that necessarily mean that it is or isn’t a “good” adaptation? Our answer: it’s not so cut and dry.

For one thing, as Gerwig says, three women’s authorship collide within one piece of work: Gerwig’s, Jo’s, and Louisa May Alcott’s. Much of “Little Women” was taken (even if modified thereafter) from Alcott’s own struggles as a woman and writer. Then, Alcott took the message and explained Jo’s point of view, after which Gerwig entered and gave her own interpretation of the narrative.

In addition to serving the story and film, Gerwig’s script’s changes were also influenced by her knowledge of the original story-teller herself. The best example of this would be the ending.

Little Women, 2019

In the “Little Women” novel, Jo March gets married and has children. Greta Gerwig took a different, and thoughtful, approach:

“One of the things that I discovered while I was researching Louisa May Alcott (and I tried to bring in a lot of this), is unlike Jo March who does get married and have children, Louisa May Alcott never got married and she never had children. But she was convinced that she needed to have Jo get married and have children in order to sell the book, but she never wanted that for her heroine. She wanted her to remain, as she called it, a literary spinster, but they convinced her no this is not gonna work so she did it the other way.”

— Greta Gerwig

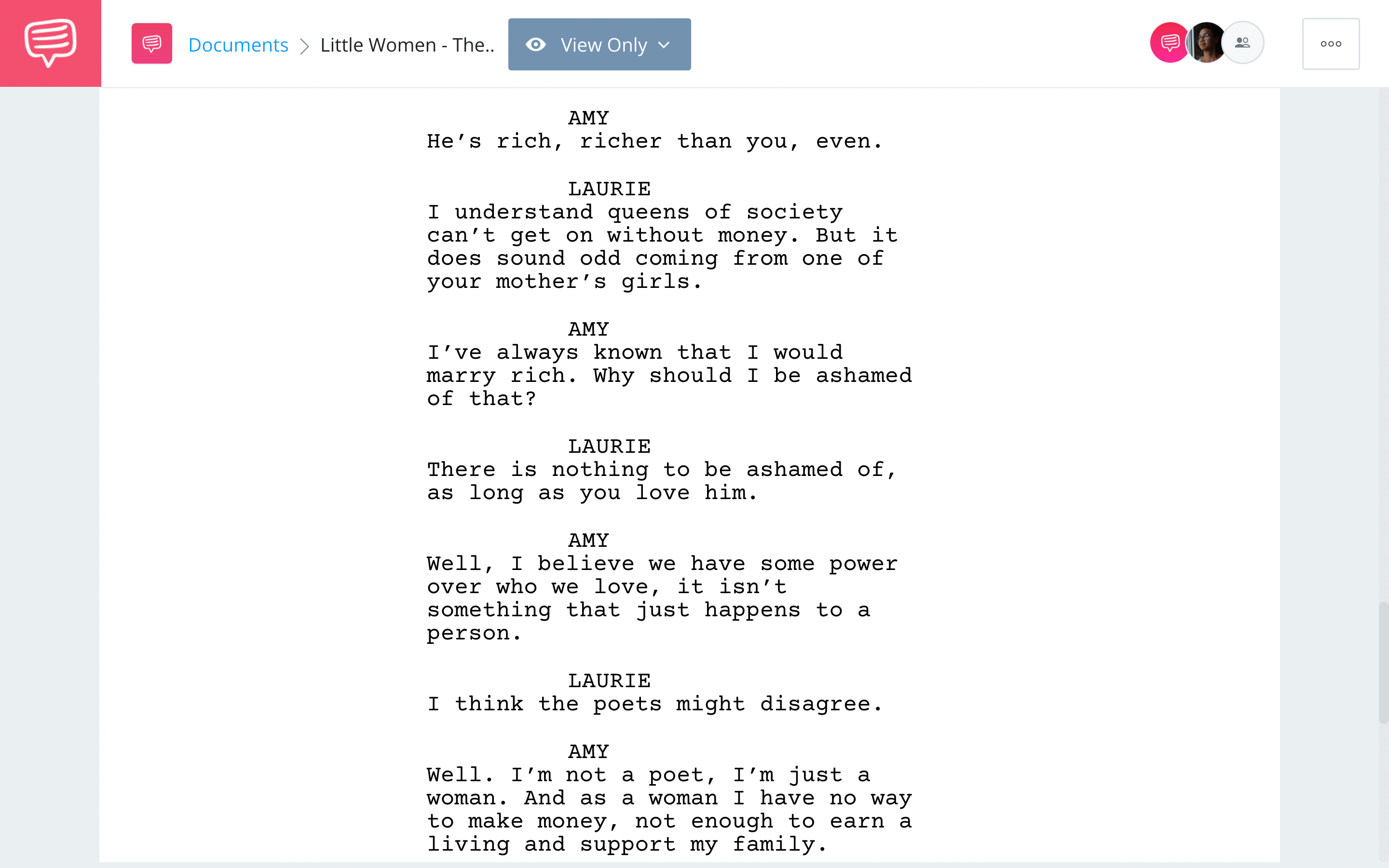

In the Little Women screenplay, Jo appears to fall in love with Friedrich. She follows him to the train station, professes her love for him, and kisses him under the umbrella in the rain. However, it soon becomes clear that Jo is recounting this tale as a potential ending for her book; this is the compromise she makes with Mr. Dashwood in order to sell her book (as well as a greater percentage of the profits and ownership of the copyright).

This is the ending Gerwig says she implemented, being that it may have been an ending the original “Little Women’ writer would have liked.

Recall that in the beginning of the script, Mr. Dashwood tells Jo, “If the main character’s a girl make sure she’s married by the end—or dead, either way.” Check out how Gerwig tampers with the slugline to show how the screenplay is taking a turn:

Little Women script • Read Little Women Creative Slugline Example

As you can see, a note to the reader is in order here, and suggests a twist that may hold ever more true to Louisa May Alcott’s vision than her own novel did. What’s especially interesting as a takeaway here is the clear shift in perspective on women there has been since “Little Women” was originally published.

Gerwig stays true to the heart of the story and makes not just quippy, naturalistic, and even modern-feeling dialogue (though much was lifted from the novel). But she also takes stock of the progress society has made and uses it to inform both her and Alcott’s visions of female artists.

Little Women Script Takeaway #3

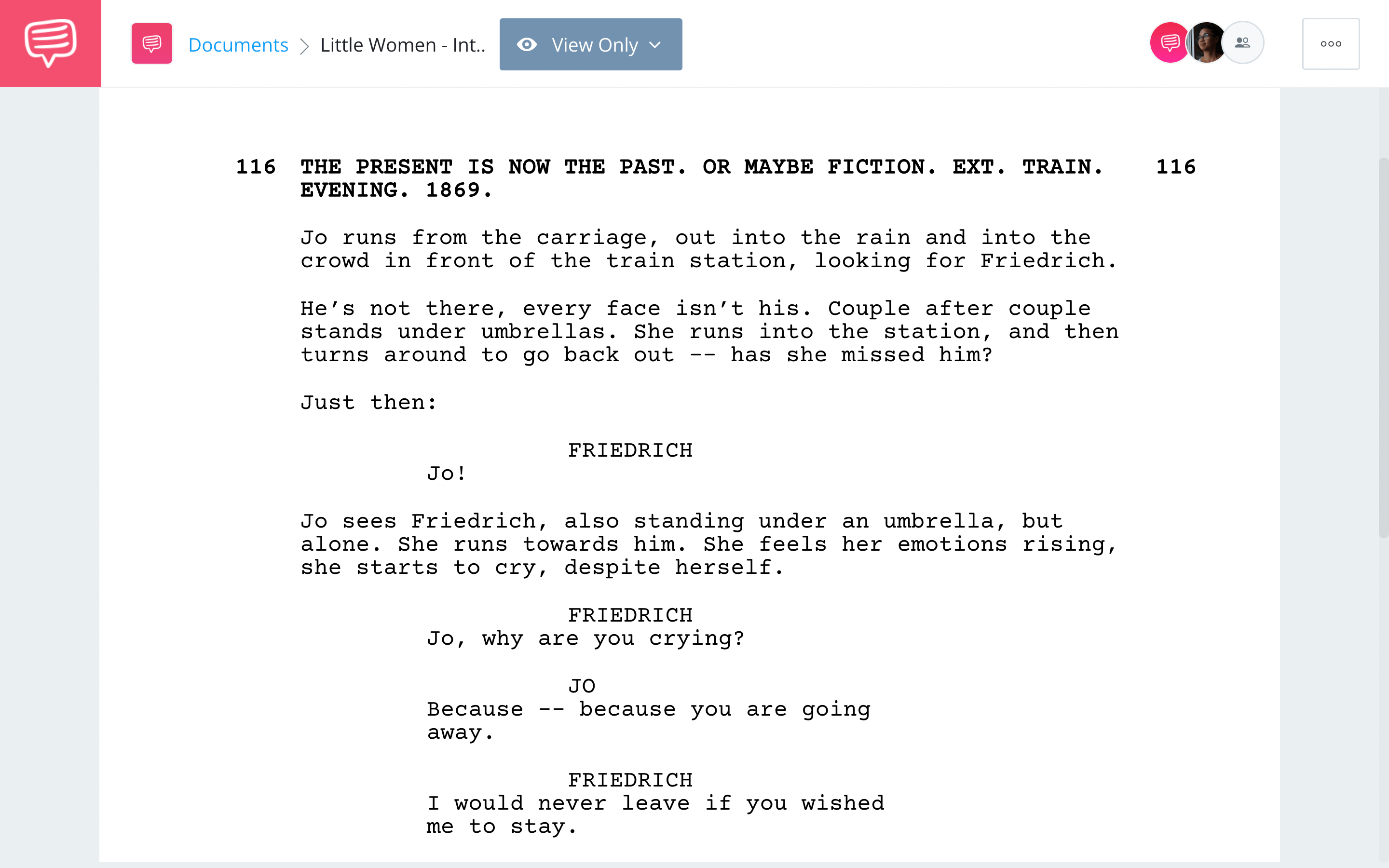

Little Women parallel timelines

If unpacking the Little Women screenplay is your focus, you can’t ignore the mosaic-like structure of its parallel timelines. In this script, action progresses forward from its point of origin, but there are two points of origin and they begin seven years apart. See below how Gerwig differentiated between the two.Little Women script • Read Parallel Timelines Note

Before the story even begins, Gerwig establishes the “rules” of reading the script. Combined with the different color text, she also points out the time period in the sluglines themselves.

Little Women script • Read Little Women Multiple Timeline Example

What’s the purpose of this time-hopping though? On the one hand, it lends itself to compounding tension. Consider for example the two scenes (linked below) in which Jo wakes up and Beth is gone.

Little Women • Beth's Last Christmas Scene

Not only does this sequence add immensely to the emotional arc of the story, but it shows contrast between characters at two different points in their lives. It provides space for nuance (especially with regard to characters), and makes the build to the narrative’s climax unique and especially rewarding.

The Little Women script may be “yet another” retelling of a story we’ve been told a million times, but the combination of timeline-hopping structure, thematic elements, and strategic adaptation of a famous literary work culminates in a beautiful story about authorship and autonomy.

These tools proved critical to the Little Women screenplay, and it proves that very old stories can have new life with timeless meaning.

Related Posts

Up Next

Read and download more scripts

Little Women is one of many exemplary adaptations based on novels and real life, alike. If you want to continue reading screenplays, we have similar titles like La La Land, (500) Days of Summer, and Little Miss Sunshine in our screenplay database. Browse and download PDFs for all of our scripts as you read, write and practice your craft to become the next great screenwriter.